| In office 12 August 2004 – 21 May 2011 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | New title |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| In office 28 November 1990 – 12 August 2004 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | |

| In office 5 June 1959 – 28 November 1990 | |

| President | |

| Deputy | See list |

| Succeeded by | |

| In office 21 November 1954 – 1 November 1992 | |

| Succeeded by | Goh Chok Tong |

| Assumed office 2 April 1955 | |

| Majority | Walkover |

| Personal details | |

| Born | |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Religion | Agnostic[1] |

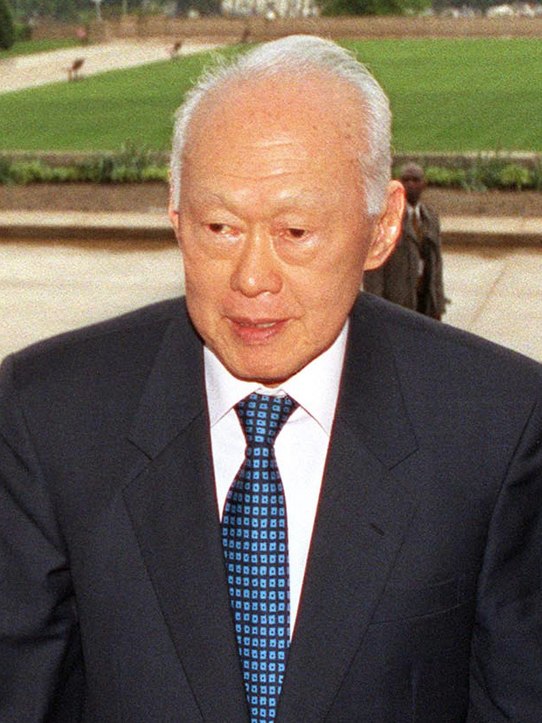

| Lee Kuan Yew |

Lee Kuan Yew, GCMG, CH (Chinese: 李光耀; pinyin: Lǐ Guāngyào; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lí Kong-iāu, English name: Harry, born 16 September 1923; also Lee Kwan-Yew) is a Singaporean statesman.[2][3][4][5] He was the first Prime Minister of the Republic of Singapore, governing for three decades. By the time he chose to step down to enable a stable leadership renewal, he had become the world's longest-serving Prime Minister.[6]

As the co-founder and first secretary-general of the People's Action Party (PAP), he led the party to eight victories from 1959 to 1990, and oversaw the separation of Singapore from Malaysia in 1965 and its subsequent transformation from a relatively underdeveloped colonial outpost with no natural resources into a "First World" Asian Tiger. He has remained one of the most influential political figures in South-East Asia.[7]

Singapore's second prime minister, Goh Chok Tong, appointed him as Senior Minister in 1990. He held the advisory post of Minister Mentor, created by his son, Lee Hsien Loong, when the latter became the nation's third prime minister in August 2004.[8][9] With his successive ministerial positions spanning over 50 years, Lee is also one of history's longest serving ministers. On 14 May 2011, Lee and Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong announced their retirement from the cabinet after the 2011 General Election.[10]

Family background

In his memoirs, Lee refers to his immigrant background as a fourth-generation Chinese Singaporean: his Hakka great-grandfather, Lee Bok Boon (born 1846), emigrated from the Dapu county of Guangdong province to the Straits Settlements in 1862.

His elder son Lee Hsien Loong has been Prime Minister of Singapore since 2004.

The eldest child of Lee Chin Koon and Chua Jim Neo, Lee Kuan Yew was born at 92 Kampong Java Road in Singapore, in a large and airy bungalow. As a child he was strongly influenced by British culture, due in part to his grandfather, Lee Hoon Leong, who had given his sons an English education. His grandfather gave him the name "Harry" in addition to his Chinese name (given by his father) Kuan Yew. He was mostly known as "Harry Lee" for his first 30 or so years, and still is to his friends in the West and to many close friends and family.[7] He started using his Chinese name after entering politics. His name is sometimes cited as Harry Lee Kuan Yew, although this first name is seldom used in official settings. Lee and his wife Kwa Geok Choo were married on 30 September 1950. His wife passed away on 2 October 2010 in her sleep. They have two sons and one daughter.[11]

Several members of Lee's family hold prominent positions in Singaporean society, and his sons and daughter hold high government or government-linked posts. His elder son Lee Hsien Loong, a former Brigadier General, has been the Prime Minister since 2004. He is also the Deputy Chairman of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC), of which Lee himself is the chairman. Lee's younger son, Lee Hsien Yang, is also a former Brigadier General and is a former President and Chief Executive Officer of SingTel, a pan-Asian telecommunications giant and Singapore's largest company by market capitalisation (listed on the Singapore Exchange, SGX). Fifty-six percent of SingTel is owned by Temasek Holdings, a prominent government holding company with controlling stakes in a variety of very large government-linked companies such as Singapore Airlines and DBS Bank. Temasek Holdings, in turn, is run by Executive Director and C.E.O. Ho Ching, the wife of Lee Hsien Loong. Lee's daughter, Lee Wei Ling, runs the National Neuroscience Institute. Lee's wife, Kwa Geok Choo, used to be a partner of the prominent legal firm Lee & Lee.

Early life

Lee was educated at Telok Kurau Primary School, Raffles Institution (where he was a member of the 01 Raffles Scout Group), and Raffles College (now National University of Singapore). His university education was delayed by World War II and the 1942–1945 Japanese occupation of Singapore. During the occupation, he operated a successful black market business selling tapioca-based glue called Stikfas.[12] Having taken Chinese and Japanese lessons since 1942, he was able to find work transcribing Allied wire reports for the Japanese, as well as being the English-language editor on the Japanese Hodobu (報道部 – an information or propaganda department) from 1943 to 1944.[7][13] After the war, he briefly attended the London School of Economics before moving to Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, where he studied law, graduating with Double Starred First Class Honours. (He was subsequently made an honorary fellow of Fitzwilliam College.) He returned to Singapore in 1949 to practise as a lawyer in Laycock and Ong, the legal practice of John Laycock, a pioneer of multiracialism who, together with A.P. Rajah and C.C. Tan, had founded Singapore's first multiracial club open to Asians.

Early political career – 1951 to 1959

Pre-People's Action Party (PAP)

Lee's first experience with politics in Singapore was his role as election agent for John Laycock under the banner of the pro-British Progressive Party in the 1951 legislative council elections. However, Lee eventually realised the party was unlikely to win mass support, especially from the Chinese-speaking working class. This was especially important when the 1953 Rendel Constitution expanded the electoral rolls to include all local-born as voters, resulting in a significant increase in Chinese voters. His big break came when he was engaged as a legal advisor to the trade and students' unions, which provided Lee with a link to the Chinese-speaking, working-class world. Later on in his career, his People's Action Party (PAP) would use these historical links to unions as a negotiating tool in industrial disputes.

Formation of the PAP

On 12 November 1954, Lee, together with a group of fellow English-educated middle-class men whom he himself described as "beer-swilling bourgeois", formed the "socialist" PAP in an expedient alliance with the pro-communist trade unionists. This alliance was described by Lee as a marriage of convenience, since the English-educated group needed the pro-communists' mass support base while the communists needed a non-communist party leadership as a smoke screen because the Malayan Communist Party was illegal. Their common aims were to agitate for self-government and put an end to British colonial rule. An inaugural conference was held at the Victoria Memorial Hall, attended by over 1,500 supporters and trade unionists. Lee became secretary-general, a post he held until 1992, save for a brief period in 1957.

In opposition

Lee won the Tanjong Pagar seat in the 1955 elections[citation needed]. He became the opposition leader against David Saul Marshall's Labour Front-led coalition government. He was also one of PAP's representatives to the two constitutional discussions held in London over the future status of Singapore, the first led by Marshall and the second by Lim Yew Hock, Marshall's hardline successor. It was during this period that Lee had to contend with rivals from both within and outside the PAP.

Lee's position in the PAP was seriously under threat in 1957 when pro-communists took over the leadership posts, following a party conference which the party's left wing had stacked with fake members.[14] Fortunately for Lee and the party's moderate faction, Lim Yew Hock ordered a mass arrest of the pro-communists and Lee was reinstated as secretary-general. After the communist 'scare', Lee subsequently received a new, stronger mandate from his Tanjong Pagar constituents in a by-election in 1957. The communist threat within the party was temporarily removed as Lee prepared for the next round of elections.

Prime Minister, pre-independence – 1959 to 1965

Self-government administration – 1959 to 1963

In the national elections held on 1 June 1959, the PAP won 43 of the 51 seats in the legislative assembly. Singapore gained self-government with autonomy in all state matters except defence and foreign affairs, and Lee became the first Prime Minister of Singapore on 5 June 1959, taking over from Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock.[15] Before he took office, Lee demanded and secured the release of Lim Chin Siong and Devan Nair, who had been arrested earlier by Lim Yew Hock's government. Lee faced many problems after gaining self-rule for Singapore from the British, including education, housing, and unemployment.

A key event was the motion of confidence of the government in which 13 PAP assemblymen crossed party lines and abstained from voting on 21 July 1961. Together with six prominent left-leaning leaders from trade unions, the breakaway members established a new party, the pro-communist Barisan Sosialis. At its inception it had popular support rivalling that of the PAP.[citation needed] 35 of the 51 branches of PAP and 19 of its 23 organising secretaries went to the Barisan Sosialis. This event was known as The Big Split of 1961. The PAP's majority was now 26-25 in the legislative assembly.

In 1961, the PAP faced two by-election defeats as well as the defections and labour unrest by leftists.[citation needed] Lee's government was near collapse until the 1962 referendum on the issue of merger, which was a test of public confidence in the government.[citation needed]

Merger with Malaysia, then separation – 1963 to 1965

Main article: Singapore in Malaysia

After Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman proposed the formation of a federation which would include Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak in 1961, Lee began to campaign for a merger with Malaysia to end British colonial rule. He used the results of a referendum held on 1 September 1962, in which 70% of the votes were cast in support of his proposal, to demonstrate that the people supported his plan.

On 16 September 1963, Singapore became part of Malaysia. However, the union was short-lived. The Malaysian Central Government, ruled by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), became worried by the inclusion of Singapore's Chinese majority and the political challenge of the PAP in Malaysia. Lee openly opposed the bumiputra policy and used the Malaysian Solidarity Convention's famous cry of "Malaysian Malaysia!", a nation serving the Malaysian nationality, as opposed to the Malay race.

The 1964 race riots in Singapore followed, such as that on Muhammad's birthday (21 July 1964), near Kallang Gasworks, in which 23 people were killed and hundreds injured as Chinese and Malays attacked each other. It is still disputed how the riots started, and theories include a bottle being thrown into a Muslim rally by a Chinese, while others have argued that it was started by a Malay. More riots broke out in September 1964, as rioters looted cars and shops, forcing both Tunku Abdul Rahman and Lee Kuan Yew to make public appearances in order to calm the situation.

Unable to resolve the crisis, the Tunku decided to expel Singapore from Malaysia, choosing to "sever all ties with a State Government that showed no measure of loyalty to its Central Government". Lee was adamant and tried to work out a compromise, but without success. He was later convinced by Goh Keng Swee that the secession was inevitable. Lee signed a separation agreement on 7 August 1965, which discussed Singapore's post-separation relations with Malaysia in order to continue co-operation in areas such as trade and mutual defence.

The failure of the merger was a heavy blow to Lee, who believed that it was crucial for Singapore’s survival. In a televised press conference on television that day, he broke down emotionally as he formally announced the separation and the full independence of Singapore:

"For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I... I believed in Malaysian merger and unity of the two territories. You know that we, as a people are connected by geography, economics, by ties of kinship... It literally broke everything that we stood for.... Now, I, Lee Kuan Yew, as Prime Minister of Singapore, in this current capacity of mine do hereby proclaim and declare on behalf on the people and the Government of Singapore that as from today, the ninth day of August in the year one thousand nine hundred and sixty-five, Singapore shall be forever a sovereign democratic and independent nation, founded upon the principles of liberty and justice and ever seeking the welfare and happiness of the people in a most and just equal society."

On that same day, 9 August 1965, just as the press conference ended, the Malaysian Parliament passed the required resolution that would sever Singapore's ties to Malaysia as a state, and thus the Republic of Singapore was created. Singapore's lack of natural resources, a water supply that was beholden primarily to Malaysia and a very limited defensive capability were the major challenges that Lee and the Singaporean Government faced.[16]

Prime Minister, post-independence – 1965 to 1990

In his autobiography, Lee stated that he did not sleep well, and fell sick days after Singapore's independence. Upon learning of Lee's condition from the British High Commissioner to Singapore, John Robb, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson expressed concern, in response to which Lee replied:

"Do not worry about Singapore. My colleagues and I are sane, rational people even in our moments of anguish. We will weigh all possible consequences before we make any move on the political chessboard..."

Lee began to seek international recognition of Singapore's independence. Singapore joined the United Nations on 21 September 1965, and founded the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on 8 August 1967 with four other South-East Asian countries. Lee made his first official visit to Indonesia on 25 May 1973, just a few years after the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation under Sukarno's regime. Relations between Singapore and Indonesia substantially improved as subsequent visits were made between Singapore and Indonesia.

Singapore has never had a dominant culture to which immigrants could assimilate even though Malay was the dominant language at that time. Together with efforts from the government and ruling party, Lee tried to create a unique Singaporean identity in the 1970s and 1980s—one which heavily recognised racial consciousness within the umbrella of multiculturalism.

Lee and his government stressed the importance of maintaining religious tolerance and racial harmony, and they were ready to use the law to counter any threat that might incite ethnic and religious violence. For example, Lee warned against "insensitive evangelisation", by which he referred to instances of Christian proselytising directed at Malays. In 1974 the government advised the Bible Society of Singapore to stop publishing religious materials in Malay.[17]

Decisions and policies

Lee Kuan Yew had three main concerns – national security, the economy, and social issues – during his post-independence administration.

National security

The vulnerability of Singapore was deeply felt, with threats from multiple sources including the communists and Indonesia with its Confrontation stance. As Singapore gained admission to the UN, Lee quickly sought international recognition of Singapore's independence. He declared a policy of neutrality and non-alignment, following Switzerland's model.[citation needed] At the same time, he asked Goh Keng Swee to build up the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) and requested help from other countries, particularly Israel, for advice, training and facilities.

The economy

Lee always placed great importance on developing the economy, and his attention to detail on this aspect went even to the extent of connecting it with other facets of Singapore, including the country's extensive and meticulous tending of its international image of being a "Garden City"[18], something that has been sustained to this day.

Government policies

Like many countries, Singapore had problems with political corruption. Lee introduced legislation giving the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) greater power to conduct arrests, search, call up witnesses, and investigate bank accounts and income-tax returns of suspected persons and their families.

Lee believed that ministers should be well paid in order to maintain a clean and honest government. In 1994, he proposed to link the salaries of ministers, judges, and top civil servants to the salaries of top professionals in the private sector, arguing that this would help recruit and retain talent to serve in the public sector.[19]

In the late 1960s, fearing that Singapore's growing population might overburden the developing economy, Lee started a vigorous Stop at Two family planning campaign. Couples were urged to undergo sterilisation after their second child. Third or fourth children were given lower priorities in education and such families received fewer economic rebates.[19]

In 1983, Lee sparked the 'Great Marriage Debate' when he encouraged Singapore men to choose highly-educated women as wives. He was concerned that a large number of graduate women were unmarried. Some sections of the population, including graduate women, were upset by his views. Nevertheless, a match-making agency Social Development Unit (SDU) was set up to promote socialising among men and women graduates.[19] In the Graduate Mothers Scheme, Lee also introduced incentives such as tax rebates, schooling, and housing priorities for graduate mothers who had three or four children, in a reversal of the over-successful 'Stop-at-Two' family planning campaign in the 1960s and 1970s. By the late 1990s, the birth rate had fallen so low that Lee's successor Goh Chok Tong extended these incentives to all married women, and gave even more incentives, such as the 'baby bonus' scheme.[19]

Corporal punishment

Main article: Caning in Singapore

One of Lee Kuan Yew's abiding beliefs has been in the efficacy of corporal punishment in the form of caning. In his autobiography The Singapore Story he described his time at Raffles Institution in the 1930s, mentioning that he was caned there for chronic lateness by the then headmaster, D. W. McLeod. He wrote: "I bent over a chair and was given three of the best with my trousers on. I did not think he lightened his strokes. I have never understood why Western educationists are so much against corporal punishment. It did my fellow students and me no harm."[20]

Lee's government inherited judicial corporal punishment from British rule, but greatly expanded its scope. Under the British, it had been used as a penalty for offences involving personal violence, amounting to a handful of caning sentences per year. The PAP government under Lee extended its use to an ever-expanding range of crimes.[21] By 1993 it was mandatory for 42 offences and optional for a further 42.[22] Those routinely ordered by the courts to be caned now include drug addicts and illegal immigrants. From 602 canings in 1987, the figure rose to 3,244 in 1993[23] and to 6,404 in 2007.[24]

It was in 1994, with the intensely publicised caning, under that vandalism legislation, of the American teenager Michael Fay, that judicial caning came to the notice of the rest of the world.

School corporal punishment (for male students only) was likewise inherited from the British, and this is in widespread use to discipline disobedient schoolboys, still under 1957 legislation.[25] Lee also introduced caning in the Singapore Armed Forces, and Singapore is one of few countries in the world where corporal punishment is an official penalty in military discipline.[26]

Relations with Malaysia

Mahathir bin Mohamad

Lee looked forward to improving relationships with Mahathir bin Mohamad upon the latter's promotion to Deputy Prime Minister. Knowing that Mahathir was in line to become the next Prime Minister of Malaysia, Lee invited Mahathir (through the then President of Singapore Devan Nair) to visit Singapore in 1978. The first and subsequent visits improved both personal and diplomatic relationships between them. Mahathir asked Lee to cut off links with the Chinese leaders of the Democratic Action Party; in exchange, Mahathir undertook not to interfere in the affairs of Malay Singaporeans.

In June 1988, Lee and Mahathir reached an agreement in Kuala Lumpur to build the Linggui dam on the Johor River.

Senior Minister – 1990 to 2004

Lee Kuan Yew (middle) meets with U.S. Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen and Singapore's Ambassador to the U.S. Chan Heng Chee in 2000.

After leading the PAP to victory in seven elections, Lee stepped down on 28 November 1990, handing over the prime ministership to Goh Chok Tong. He was then the world's longest-serving Prime Minister.[6]

This was the first leadership transition since independence.

When Goh Chok Tong became head of government, Lee remained in the cabinet with a non-executive position of Senior Minister and played a role he described as advisory. In public, Lee would refer to Goh as "my Prime Minister", in deference to Goh's authority. He has said in a 1988 National Day rally:

"Even from my sick bed, even if you are going to lower me into the grave and I feel something is going wrong, I will get up."

Lee subsequently stepped down as the Secretary-General of the PAP and was succeeded by Goh Chok Tong in November 1992.

Minister Mentor – 2004 to 2011

Since the early 2000s, Lee has expressed concern about the declining proficiency of Mandarin among younger Chinese Singaporeans. In one of his parliamentary speeches, he said: "Singaporeans must learn to juggle English and Mandarin". Subsequently, in December 2004, a one-year long campaign called 华语 Cool! (Huayu Cool!) was launched, in an attempt to attract young viewers to learn and speak Mandarin.[27]

In June 2005, Lee published a book, Keeping My Mandarin Alive, documenting his decades of effort to master Mandarin, a language which he said he had to re-learn due to disuse:

"...because I don't use it so much, therefore it gets disused and there's language loss. Then I have to revive it. It's a terrible problem

No comments:

Post a Comment